今日推荐开源项目:《渲染库pixijs》

今日推荐英文原文:《Why do we contribute to open source software?》

今日推荐开源项目:《渲染库pixijs》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:Pixi 是一个超快的2D渲染引擎,具有强大的图片渲染能力和场景图技术。它会帮助你用 JavaScript 或者其他 HTML5 技术来显示媒体,创建动画或管理交互式图像,从而制作一个游戏或应用。最重要的的是,Pixi 没有妨碍你的编程方式,你可以自己选择使用多少它的功能,可以遵循你自己的编码风格,或让 Pixi 与其他有用的框架无缝集成。

Pixi的API比老旧的Adobe Flash API更精致,并且它是通用的:它不是一个游戏引擎,它给了你所有的自由去做任何你想做的事,甚至用它可以写成你自己的游戏引擎。

今日推荐英文原文:《Why do we contribute to open source software?》作者:Gordon Haff

原文链接:

推荐理由:程序员们为什么要加入各种开源项目并且为此投入时间、精力甚至是金钱呢?我想每一个参与者都有自己的理由。组织作为一个整体为开源软件项目做出贡献有多种原因,包括我们也是如此啊,知道自己为什么要去做,才能做得更好。

Why do we contribute to open source software?

Dive into the research supporting the open source ecosystem and developers’ motivations for participating.

(Image credits : TeroVesalainen via Pixabay CC0)

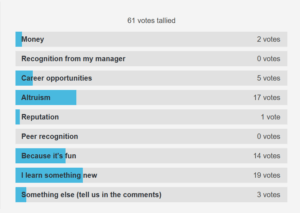

What motivates you to contribute to open source?

Organizations as a whole contribute to open source software projects for a variety of reasons.

(Screenshot from original)One of the most important is that the open source development model is such an effective way to collaborate with other companies on projects of mutual interest. But they also want to better understand the technologies they use. They also want to influence direction.

The specific rationale will vary by organization but it usually boils down to the simple fact that working in open source benefits their business.

But why do individuals contribute to open source? They mostly see some kind of personal benefit too, but what specifically motivates them?

The types of motivation

When we talk about motivations, one common way to do so is in terms of incentive theory. This theory began to emerge during the 1940s and 1950s, building on the earlier drive-reduction theories established by psychologists such as Clark Hull and Kenneth Spence. Incentive theory was originally based on the idea that motivation is largely fueled by the prospect of an external reward or incentive.Money is a classic extrinsic motivator. So is winning an award, getting a grade, or obtaining a certification that is likely to lead to a better job.

However, in the 1970s, researchers began to also consider intrinsic motivations, which do not require an apparent reward other than the activity itself. Self-determination theory, developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, would later evolve from studies comparing intrinsic and extrinsic motives, and from a growing understanding of the dominant role intrinsic motivations can play in behavior.

While intrinsic motivations can come from a number of different sources, the most straightforward one is the simple enjoyment of a particular activity. You play in a softball league after work because you like playing softball. You enjoy the exercise, the camaraderie, the game itself.

Researchers have also proposed a further distinction between this enjoyment-based intrinsic motivation and obligation/community-based intrinsic motivation, which is more about adherence to social or community norms. Maybe you don’t really like having the relatives over for Thanksgiving but you do it anyway because you know you should.

Today’s psychology literature also includes the idea of internalized extrinsic motivations. These are extrinsic motivations such as gaining skills to enhance career opportunities—but they’ve been internalized so that the motivation comes from within rather than the desire for whatever carrot is being dangled by someone else.

What motivates open source developers?

In 2012, four researchers at ETH Zurich surveyed the prior ten years of study into open source software contribution. Among their results, they were able to group study findings into the following three categories: extrinsic motivation, intrinsic motivation, and internalized extrinsic motivation—as well as some common sub-groupings within those broader categories.No surprise that money showed up as an extrinsic motivator. During the period studied, there were fewer large projects associated with successful commercially-supported products than is the case today. Even so, most of the open source projects the researchers examined had a significant number of contributors whose companies had paid them to work on open source.

Career obviously goes hand in hand with pay, but is open source software any different from proprietary software development in this regard? There’s some evidence that it is.

Lerner and Tirole first suggested in 2002 that "individual developers would be motivated by career concerns when developing open source software. By publishing software that was free for all to inspect, they could signal their talent to potential employers and thus increase their value in the labor market."

More recently, there’s been significant empirical evidence that there are career advantages to developing code and making it available for others to see and work with. It has become almost an expectation in some industry segments for job applicants to have public GitHub code repositories, which are effectively part of their resume.

It’s reasonable to ask whether this trend has gone too far. After all, many highly qualified developers work on proprietary code. But it’s clear that, fair or not, at least some career prospects can come specifically from being an open source developer.

Among intrinsic motivators, ideology and altruism often seem closely related.

Free software was primarily an ideological statement at first, even if user control also had an important practical side; several researchers have found support for ideological motives in developer surveys.

Altruism can also be a developer motive, though research on this is mixed. One paper identified the “desire to give a present to the programmer community” as a crucial pattern in open source software. But other studies have qualified the importance of altruism as a motive, especially among programmers getting a paycheck. Other work found that altruism could be a motivator but only among developers who were otherwise satisfied.

There’s also the motivational power of fun and enjoyment, a classic intrinsic motivator. This should come as no surprise to anyone who hangs around open source developers. Almost all of them like working on open source projects. One large 2007 study determined that fun accounted for 28 percent of the effort (in terms of number of hours) dedicated to projects. One implication of this research is that activities developers typically enjoy less–tech support often tops this list–may require alternative forms of motivation.

Much of the research into reputation as an internalized extrinsic motivator has focused specifically on peer recognition. Your reputation among your peers can be a source of your own pride, but it also signals your talent to community insiders and potential employers. The suggestion that reputation could be an important motivator in contributing to open source goes back at least as far as 1998, in Eric Raymond’s essay "Homesteading the Noosphere." However, since then, a variety of surveys have supported the idea that peer reputation is a driver for participation.

Another motivator in this category is what researchers call "own-use value" but is more recognizably described as something like "scratch your own itch"–develop something that you want for yourself and in the process, create something valuable to others. The initial motivation essentially comes from a selfish need but that can evolve into more of an internalized desire to contribute.

It's unsurprising research would identify own-use value as a good motivator. Certainly, the folk wisdom is that many developers get into open source by developing something they themselves need—such as when Linus Torvalds wrote Git because Linux needed an appropriate distributed version control system.

As we’ve seen, contributors to open source software have a variety of different motivations but there are a few general threads worth highlighting in closing.

Motivators can actually be counterproductive when a single motivator is relied upon too heavily. One study reported that developers scratching their own itch worked "eclectically," fixing bugs that annoyed them and then quitting until the next time.

In particular, don’t expect non-extrinsic motivators to carry too much of the load. Fun isn’t a good motivator if the task is not actually fun. Altruism motivates some but it also doesn’t pay their bills.

That said, developers do contribute for reasons that aren’t purely about money or other extrinsic reasons. Learning, peer reputation, and recognition are important to many (and not just in open source development.) Organizations should not neglect the role these can play in motivating developers and should implement incentive programs around them, such as peer reward systems.

下载开源日报APP:https://openingsource.org/2579/

加入我们:https://openingsource.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://openingsource.org/about/love/