今日推荐开源项目:《美观模板 readme-md-generator》

今日推荐英文原文:《Why people will beat machines in recognising speech for a long time yet》

今日推荐开源项目:《美观模板 readme-md-generator》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:每个 GitHub 项目都不会把 Readme 给落下的,这个项目能够让你按照模版生成一个 Readme.md,你只需要像写填空题一样把它填满就好。每个项目的 Readme 如同矛盾一样,具有共性和个性,共性是指每个项目都有安装方法和版本号等等这些方面,而个性则是每个项目的特性等都不相同,共性和个性是相互渗透,相互影响的,在一定条件下也可能相互转化。

今日推荐英文原文:《Why people will beat machines in recognising speech for a long time yet》作者:Edge

原文链接:https://medium.com/edge/why-people-will-beat-machines-in-recognising-speech-for-a-long-time-yet-115e8dd09690

推荐理由:说话的语音变化对于人类来说可能可以识别,但是对于机器来说可能并非如此

Why people will beat machines in recognising speech for a long time yet

Imagine a world in which Siri always understands you, Google Translate works perfectly, and the two of them create something akin to a Doctor Who style translation circuit. Imagine being able to communicate freely wherever you go (not having to mutter in school French to your Parisian waiter). It’s an attractive, but still distant prospect. One of the bottlenecks in moving this reality forward is variation in language, especially spoken language. Technology cannot quite cope with it.Humans, on the other hand, are amazingly good at dealing with variations in language. We are so good, in fact, that we really take note when things occasionally break down. When I visited New Zealand, I thought for a while that people were calling me “pet”, a Newcastle-like term of endearment. They were, in fact, just saying my name, Pat. My aha moment happened in a coffee shop (“Flat white for pet!” gave me a pause).

This story illustrates how different accents of English have slightly different vowels — a well-known fact. But let’s try to understand what happened when I misheard the Kiwi pronunciation of Pat as pet. There is a certain range of sounds that we associate with vowels, like a or e. These ranges are not absolute. Rather, their boundaries vary, for instance between different accents. When listeners fail to adjust for this, as I did in this case, the mapping of sound to meaning can be distorted.

One could, laboriously, teach different accents to a speech recognition system, but accent variation is just the tip of the iceberg. Vowel sounds can also vary depending on our age, gender, social class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, level of intoxication, how fast we are talking, whom we are talking to, whether or not we are in a noisy environment … the list just goes on, and on.

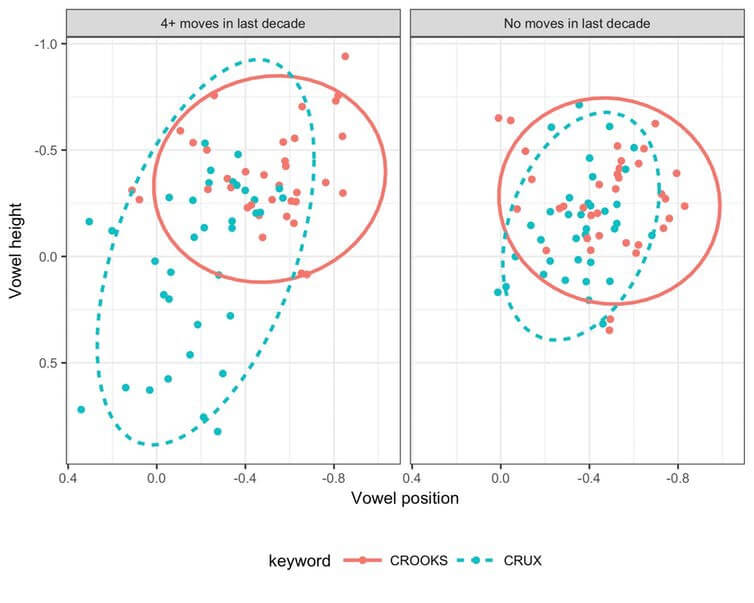

The crux/crooks of the matter

Consider that a recent study I was involved in showed that even moving house (or not) can affect one’s vowels. Specifically, there is a correlation between how speakers of Northern English pronounce the vowel in words like crux, and how many times they have moved in the last decade. People who have not moved at all are more likely to pronounce crux the same as crooks, which is the traditional Northern English pronunciation. But those who have moved four times or more are more likely to have different vowels in the two words, similarly in the south of England.There is, of course, nothing about the act of moving that causes this. But moving house multiple times is correlated with other lifestyle factors, for instance interacting with more people, including people with different accents, which might influence the way we speak.

Other sources of variation may have to do with linguistic factors, such as word structure. A striking example comes from pairs of words such as ruler, meaning “measuring device” and ruler, meaning “leader”.

These two words are superficially identical, but they differ at a deeper structural level. A rul-er is someone who rules, just like a sing-er is someone who sings, so we can analyse these words as consisting of two meaningful units. In contrast, ruler meaning “measuring device” cannot be decomposed further.

It turns out that the two meanings of ruler are associated with a different vowel for many speakers of Southern British English, and the difference between the two words has increased in recent years: it is larger for younger speakers than it is for older speakers. So both hidden linguistic structure and speaker age can affect the way we pronounce certain vowels.

End never in sight

This illustrates another important property of language variation: it keeps changing. Language researchers therefore constantly have to review their understanding of variation, which in turn requires continuing to acquire new data, and updating the analysis. The way we do this in linguistics is being revolutionised by new technologies, advances in instrumental data analysis, and the ubiquity of recording equipment (in 2018, 82% of the UK adult population owned a recording device, otherwise known as a smartphone).Modern day linguistic projects can profit from the technological advancement in various ways. For instance, the English Dialects App collects recordings remotely via smartphones, to build a large and constantly updating corpus of modern day English accents. That corpus is the source of the finding concerning the vowel in crux in Northern English, for example. Accumulating information from this and many other projects allows us to track variation with increased coverage, and to build ever more accurate models predicting the realisation of individual sounds.

Can this newly refined linguistic understanding also improve speech recognition technology? Perhaps, but in order to improve, the technology needs to know a lot more about you.

下载开源日报APP:https://openingsource.org/2579/

加入我们:https://openingsource.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://openingsource.org/about/love/