今日推荐开源项目:《象棋 awesome-chess》

今日推荐英文原文:《TDD Changed My Life》

今日推荐开源项目:《象棋 awesome-chess》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:相信大家小时候都有看到过街边老人们摆出象棋决斗的经历,这次要推荐的项目就是关于象棋的资源合集——虽然是国际象棋。国际象棋的下法与中国象棋有不少相似之处,比如能十字前进的车与走日字的马,不过因为存在王车易位和兵的升变这样的特殊行动方式,实际玩起来和象棋还是有很大差距的,作为平时休闲娱乐的手段尝试一下也无妨。

今日推荐英文原文:《TDD Changed My Life》作者:Eric Elliott

原文链接:https://medium.com/javascript-scene/tdd-changed-my-life-5af0ce099f80

推荐理由:介绍了 TDD——Test Driven Development 的优点

TDD Changed My Life

It’s 7:15 am and customer support is swamped. We just got featured on Good Morning America, and a whole bunch of first time customers are bumping into bugs.It’s all-hands-on-deck. We’re going to ship a hot fix NOW before the opportunity to convert more new users is gone. One of the developers has implemented a change he thinks will fix the issue. We paste the staging link in company chat and ask everybody to go test the fix before we push it live to production. It works!

Our ops superhero fires up his deploy scripts, and minutes later, the change is live. Suddenly, customer support call volume doubles. Our hot-fix broke something else, and the developers erupt in synchronized git blame while the ops hero reverts the change.

Why TDD?

It’s been a while since I’ve had to deal with that situation. Not because developers stopped making mistakes, but because for years now, every team I’ve led and worked on has had a policy of using TDD. Bugs still happen, of course, but the release of show-stopping bugs to production has dropped to near zero, even though the rate of software change and upgrade maintenance burden has increased exponentially since then.Whenever somebody asks me why they should bother with TDD, I’m reminded of this story — and dozens more like it. One of the primary reasons I switched to TDD is for improved test coverage, which leads to 40%-80% fewer bugs in production. This is my favorite benefit of TDD. It’s like a giant weight lifting off your shoulders.

TDD eradicates fear of change.On my projects, our suites of automated unit and functional tests prevent disastrous breaking changes from happening on a near-daily basis. For example, I’m currently looking at 10 automated library upgrades from the past week that I used to be paranoid about merging because what if it broke something?

All of those upgrades integrated automatically, and they’re already live in production. I didn’t look at a single one of them manually, and I’m not worried at all about them. I didn’t have to go hunting to come up with this example. I popped open GitHub, looked at recent merges, and there they were. What was once manual maintenance (or worse, neglect) is now automated background process. You could try that without good test coverage, but I wouldn’t recommend it.

What is TDD?

TDD stands for Test Driven Development. The process is simple:

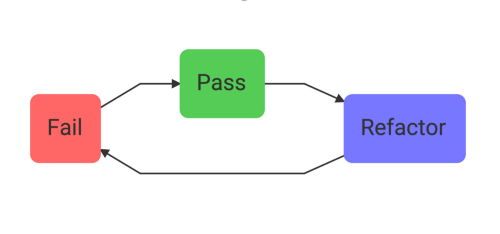

Red, Green, Refactor

- Before you write implementation code, write some code that proves that the implementation works or fails. Watch the test fail before moving to the next step (this is how we know that a passing test is not a false positive — how we test our tests).

- Write the implementation code and watch the test pass.

- Refactor if needed. You should feel confident refactoring your code now that you have a test to tell you if you’ve broken something.

How TDD Can Save You Development Time

On the surface, it may seem that writing all those tests is a lot of extra code, and all that extra code takes extra time. At first, this was true for me, as I struggled to understand how to write testable code in the first place, and struggled to understand how to add tests to code that was already written.TDD has a learning curve, and while you’re climbing that learning curve, it can and frequently does add 15% — 35% to implementation times. But somewhere around the 2-years in mark, something magical started to happen: I started coding faster with unit tests than I ever did without them.

Several years ago I was building a video clip range feature in a UI. The idea was that you’d set a starting point for a video, and and ending point, and when the user links to it, it would link to that precise clip, rather than the whole video.

But it wasn’t working. The player would reach the end of the clip and keep on playing, and I had no idea why.

I kept thinking it had to do with the event listener not getting hooked up properly. My code look something like this:

video.addEventListener('timeupdate', () => {

if (video.currentTime >= clip.stopTime) {

video.pause();

}

});

Each change took almost a minute to test, and I tried a hilariously large number of things (most of them 2–3 times).

Did I misspell timeupdate? Did I get the API right? Is the video.pause() call working? I’d make a change, add a console.log(), jump back into the browser, hit refresh, click to a moment before the end of the clip, and then wait patiently for it to hit the end. Logging inside the if statement did nothing. OK, that’s a clue. Copy and paste timeupdate from the API docs to be absolutely sure it wasn’t a typo. Refresh, click, wait. No luck!

Finally, I placed a console.log() outside the if statement. “This can’t help,” I thought. After all, that if statement was so simple, there’s no way I could have screwed up the logic. It logged. I spit my coffee on the keyboard. WTF?!

Murphy’s Law of Debugging: The thing you believe so deeply can’t possibly be wrong so you never bother testing it is definitely where you’ll find the bug after you pound your head on your desk and change it only because you’ve tried everything else you can possibly think of.I set a breakpoint to figure out what was going on. I inspected the value of clip.stopTime. undefined??? I looked back at my code. When the user clicks to select the stop time, it places the little stop cursor icon, but never sets clip.stopTime. “OMG I’m a gigantic idiot and nobody should ever let me anywhere near a computer again for as long as I live.”

Years later I still remember this because of that feeling. You know exactly what I’m talking about. We’ve all been there. We’re all living memes.

Actual photos of me while I’m coding.

If I was writing that UI today, I’d start with something like this:

describe('clipReducer/setClipStopTime', async assert => {

const stopTime = 5;

const clipState = {

startTime: 2,

stopTime: Infinity

};

assert({

given: 'clip stop time',

should: 'set clip stop time in state',

actual: clipReducer(clipState, setClipStopTime(stopTime)),

expected: { ...clipState, stopTime }

});

});

Note: Want to write unit tests like this? Check out “Rethinking Unit Test Assertions”.The point is not how long it takes to type this code. The point is how long it takes to debug it if something goes wrong. If this code broke, this test would give me a great bug report. I’d know right away that the problem is not the event handler. I’d know it’s in setClipStopTime() or the clipReducer() which implements the state mutation. I’d know what it’s supposed to do, the actual output, and the expected output — and more importantly — so would a coworker, 6-months into the future who’s trying to add features to the code I built.

One of the first things I do in every project is set up a watch script that automatically runs my unit tests on every file change. I often code with two monitors side-by-side and keep my dev console with the watch script running on one monitor while I code on the other. When I make a change, I usually know within 3 seconds whether or not that change worked.

For me, TDD is far more than a safety net. It’s also constant, fast, realtime feedback. Instant gratification when I get it right. Instant, descriptive bug report when I get it wrong.

TDD Taught Me How to Write Better Code

I’m going to admit something embarrassing: I had no idea how to build apps before I learned TDD with unit testing. How I ever got hired would be beyond me, but after interviewing hundreds and hundreds of developers, I can tell you with great confidence: there are a lot of developers in the same boat. TDD taught me almost everything I know about effective decoupling and composition of software components (meaning modules, functions, objects, UI components, etc.)The reason for that is because unit tests force you to test components in isolation from each other, and from I/O. Given some input, the unit under test should produce some known output. If it doesn’t, the test fails. If it does, it passes. The key is that it should do so independent of the rest of the application. If you’re testing state logic, you should be able to test it without rendering anything to the screen or saving anything to a database. If you’re testing UI rendering, you should be able to test it without loading the page in a browser or hitting the network.

Among other things, TDD taught me that life gets a lot simpler when you keep UI components as minimal as you can. Isolate business logic and side-effects from UI. In practical terms, that means that if you’re using a component-based UI framework like React or Angular, it may be advantageous to create display components and container components, and keep them separate.

For display components, given some props, always render the same state. Those components can be easily unit tested to be sure that props are correctly wired up, and that any conditional logic in the UI layout works correctly (for example, maybe a list component shouldn’t render at all if the list is empty, and it should instead render an invitation to add some things to the list).

I knew about separation of concerns long before I learned TDD, but I didn’t know how to separate concerns.

Unit testing taught me about using mocks to test things, and then it taught me that mocking is a code smell, and that blew my mind and completely changed how I approach software composition.

All software development is composition: the process of breaking large problems down into lots of small, easy-to-solve problems, and then composing solutions to those problems to form the application. Mocking for the sake of unit tests is an indication that your atomic units of composition are not really atomic, and learning how to eradicate mocks without sacrificing test coverage taught me how to spot a myriad of sneaky sources of tight coupling.

That has made me a much better developer, and taught me how to write much simpler code that is easier to extend, maintain, and scale, both in complexity, and across large distributed systems like cloud infrastructure.

How TDD Saves Whole Teams Time

I mentioned before that testing first leads to improved test coverage. The reason for that is that we don’t start writing the implementation code until we’ve written a test to ensure that it works. First, write the test. Then watch it fail. Then write the implementation code. Fail, pass, refactor, repeat.That process builds a safety net that few bugs will slip through, and that safety net has a magical impact on the whole team. It eliminates fear of the merge button.

That reassuring coverage number gives your whole team the confidence to stop gatekeeping every little change to the codebase and let changes thrive.

Removing fear of change is like oiling a machine. If you don’t do it, the machine grinds to a halt until you clean it up and crank it, squeaking and grinding back into motion.

Without that fear, the development cadence runs a lot smoother. Pull requests stop backing up. Your CI/CD is running your tests — it will halt if your tests fail. It will fail loudly, and point out what went wrong when it does.

And that has made all the difference.

下载开源日报APP:https://openingsource.org/2579/

加入我们:https://openingsource.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://openingsource.org/about/love/