今日推荐开源项目:《玩中学 awesome-eg》

今日推荐英文原文:《Innovation isn’t what you think it is》

今日推荐开源项目:《玩中学 awesome-eg》传送门:GitHub链接

推荐理由:一边玩游戏一边学习何乐而不为呢?这个项目是关于那些带有教育作用的游戏的集合,让你可以一边玩游戏一边学到各种知识,包括常见的编程和其他音乐美术这些方面,如果这里面刚好有你感兴趣的内容的话,不妨可以尝试一下。

今日推荐英文原文:《Innovation isn’t what you think it is》作者:Richard W. DeVaul

原文链接:https://medium.com/@devaul/https-medium-com-devaul-innovation-isnt-what-you-think-it-is-52f03a9d2d7d

推荐理由:每个人对于创新是什么都有不同的见解,作者也是如此

Innovation isn’t what you think it is

his essay is one in a series of essays inspired by two decades of experience as an innovation professional, spanning domains from academic to corporate, technical subject areas ranging from consumer electronics to high altitude ballooning, and organizational structures from small teams and startups to fortune 100 companies. I’ve had successes and failures, launched and killed projects and companies. I’ve had the privilege of working with amazing teams, colleagues, and mentors. As a consequence of all of this I’ve learned a lot. In this essay series I explore innovation leadership and innovation culture from the perspective of in-the-trenches lived experience. After all, why should you repeat my mistakes when there are so many interesting new mistakes to be made?introduction

As an executive innovation consultant, CEOs and business leaders come to me for help in setting up innovation labs, fixing broken organizational process around innovation, or building innovation teams. They have dreams of turning their organization into the next Apple or Bell Labs. There’s just one problem with their innovation dreams: they’ve got the concept of “innovation” all wrong.What is innovation? If you think innovation is simply making something new, you are missing a central, terrifying idea. The long history of innovation has proven time and again that innovation isn’t about making something new, it is about destroying the existing order of things. This is why almost every established organization is inherently innovation-averse; innovation is an existential threat to incumbents, including incumbent innovators. Don’t believe me? Ask Eastman Kodak, the leading film photography company for more than a century who invented the first self-contained digital camera in 1975, and subsequently declared bankruptcy in 2012, having failed to compete in the digital photography world they helped to create.

I’m not trying to scare you out of innovation. I want you to understand what innovation means, so you can formulate the right strategy for your organization. I want you to understand the costs, benefits, and risks of the various options. Because even if you aren’t innovating, your competitors certainly will be. Change isn’t optional; the question is whether you will drive that change or react to the change. Both approaches have benefits, challenges, and limitations. The third option is to be overwhelmed by change. That’s what happens if you don’t have a strategy.

Let’s begin with a story:

innovation case study: Xerox PARC and the rise of the Digital Age

You probably know at least some of this story. Xerox was the dominant company in the domains of paper document copying and transmission in the 50s and 60s. In 1970, visionary leaders of Xerox founded Xerox PARC, the Palo Alto Research Center, located far away from Xerox corporate headquarters and situated in the heart of nascent Silicon Valley.

The short version is that in the short span of about a decade PARC researchers invented nearly everything important in the digital revolution prior to mobile, with the exception of Internet protocols (these were developed by BBN Technologies in 1968, at the behest of ARPA). Xerox PARC’s contributions spanned the core technologies of personal computers, Ethernet networking, laser printing (plus page description language), the graphical user interface based on windows, icons, mouse, and pointer — just to name a few. And yet, Xerox was not the first great personal computer company, or local area network company, or GUI company, or even laser printing company. Xerox invented everything, and others capitalized on these inventions.

There is a myth that Steve Jobs visited Xerox PARC in 1979 and discovered all of these things. This is probably just a myth, but it is well documented that a number of Xerox PARC employees left PARC and joined Apple in the early days. Regardless, the beneficiaries of PARC’s inventions were primarily Apple and IBM and Microsoft and Adobe, among others. Not Xerox.

Xerox and PARC still exist. There is still a market for photocopiers. But Xerox in every meaningful way failed to capitalize on their massive disruptive innovation, and was not a significant market player in the digital revolution that they very invented.

why innovation is terrifying

As our story shows, the worst part is that it isn’t generally possible to know or predict what will be destroyed by a true innovation before it is released into the wild. The transformation of documents from paper to digital wasn’t anticipated by Xerox leadership, certainly not on the rapid timescale of the digital revolution. Had it been, it is dubious that the “document company” would have ever gotten into digital technology research. As it worked out, Xerox invented the future and made itself obsolete at the same time.When you innovate, maybe the result will be a new line of business. Maybe it will make some other line of business obsolete. Maybe it will put you out of business, and the benefits will be reaped by a more agile competitor. The outcome depends on how your organization recognizes and responds to change.

who am I to tell you?

I’ve spent nearly two decades working in the technology innovation space. Beginning as a graduate student at the MIT Media Lab doing wearables in the late 90s, to a stint in startup-land (and the great recession of 2008) to Apple to Google, I’ve been fortunate to work in some of the most forward-thinking places, cultures, and organizations on the planet. I’ve seen successes and failures, founded billion-dollar business and laid off my friends. I’ve gotten lucky, made lots of mistakes, and learned a great deal — both about what works and what doesn’t work. And perhaps most importantly, I’ve learned the cost and benefits of creating and nurturing innovation inside a range of different organizations, from academic labs to startups to Fortune 100 companies.and who are you?

You are a corporate executive, manager, or leader who is interested in making large scale, fundamental change, or who is navigating a path for your organization in a changing landscape. You know you need a strategy for innovation and must decide whether and how to invest in the future. Hoping that things work out OK isn’t a strategy.

why your organization sucks at innovation

It is extremely difficult to make or deliver something radically new without embracing profound organizational changes along the way and sacrificing some of your existing investments or opportunities. And if that doesn’t sound appealing, a refusal to embrace change has even more dire consequences.

Rejecting innovation is always easier than embracing it, for almost any organization under almost any circumstances. It’s also potentially lethal. To accept real innovation (and the organizational stress that inevitably entails) requires a process and culture, backed by strong leadership. This combination of “bottom up” (culture/process) and “top down” (leadership) was brilliantly exemplified by Apple under Steve Jobs. But it doesn’t require legendary leadership if process is good — for example, the US Army is remarkably good at systematic, effective innovation. They have internalized that they either learn or die.

So, how do you create and support an effective innovation culture? That is the subject of its own essay, coming soon.

I think I hear someone saying, “but I don’t want to have to restructure my organization or throw away my existing opportunities, I want the positive benefits of change without the potential complications or the costs of radical disruption.” In that case, you don’t want radical change. What you want is incrementalism. And while you won’t be redefining a field or changing an industry, you can create a lot of value with incremental change. As long as Henry Ford doesn’t pull the rug out from under your incrementally better buggy whips by introducing the Model T.

innovation vs incrementalism

Much of the time, the “innovation” that companies or organizations want and would benefit the most from isn’t really innovation at all. It is the incremental improvement of something that already exists. There is nothing wrong with this. In fact, it’s great. Incrementalism is a generally the best way to generate value and returns while leveraging your existing investment and minimizing stress and disruption in the organization. Most of the time incrementalism, not innovation, is the rational thing for organizations to focus on. It’s not sexy to talk about incrementalism but it probably should be — it’s where most of the value in the world comes from. And in markets or industries that are stable, incrementalism is where it’s at.

Here is an analogy: If you were a so-so investment banker, should you focus on building your investment banking skills, or should you throw it all away to become a professional Flamenco guitarist? Surely, for most people the path of wisdom (or at least a bigger paycheck) would be the incremental path. There may be times to do the latter, but you should think hard before making that decision. Likewise, if you had an established career in music, should you throw it away to become a banker? The expected paycheck might be bigger in the long run, but barriers to entry in your new profession are high. Furthermore, a lot of your existing investments in skills, relationships, and musical gear won’t translate. What about trying to do both? That’s tricky — trying to successfully develop new skills and opportunities while maintaining the status quo is likely to leave you as a mediocre banker and a mediocre professional musician.

The choice I’ve described above in personal terms is also true for organizations. Trying to develop new organizational competencies while also pursuing a separate main line of business can be like studying banking while trying to keep up with the demands of being a touring musician. In the short run it’s going to be costly and stressful even if it pays off in the long run.

But incrementalism offers a path to making steady improvements, which over time can add up to a big deal. Others have written about the value of incremental improvement in your organization or in your personal habits. If there is a goal you can feasibly reach through an incremental approach vs. a more radical one, incrementalism is almost always the better choice.

So, what are the downsides to incrementalism? At the end of the day, incremental value creation works only for as long as line of business or market is stable. Some markets are stable for decades — think of the film industry during the heyday of Kodak. But eventually, things change. Either you can be surprised by the change, or you can embrace the change, or you can drive the change. The problem is that most large organizations, even ones with spare cycles for advanced development, are too slow to adapt, e.g. Kodak. But not always. Consider the case study of Microsoft and Internet Explorer.

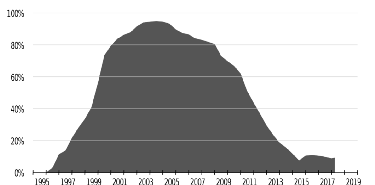

innovation case study: Microsoft and Internet Explorer

The year is 1993. The online world is tiny and dominated by Compuserve, Prodigy, and AOL. Really hip people are on The Well. The world wide web exists, but outside a small academic community and a few nerds nobody has heard of it. Then an open-source web browser named Mosaic is released, combining the ability to view text and graphics together in hyperlinked documents. The popularity of hypertext begins to grow. In 1994, Netscape Communications ships the first commercial web browser, Navigator, and the web starts to take off.

Microsoft Internet Explorer market share (credit: El T)

In 1995 Microsoft ships its first browser, Internet Explorer version 1, along with the new Windows ’95 operating system. Nobody uses IE 1, as Netscape dominates the small but rapidly growing online world. Undeterred, Microsoft copies most of the features of Netscape for IE2 and IE3, heavily promoting its own browser through bundling with its operating system products. It’s market share rises. Eventually, Microsoft and IE dominate the online world, and Netscape fades into obscurity.

Microsoft didn’t invent the world wide web. It didn’t create the first popular web browser. It’s first browser offering was feature poor and unpopular. But through grit, tenacity, and (potentially unfair) bundling tactics, Microsoft won the “browser wars” and relegated Netscape and Mosaic to obscurity. Of course, IE itself was eventually displaced by Google’s Chrome, but that is another story. The point is that Microsoft wasn’t a first mover, maybe not even a second mover. Microsoft was a large company that was late to the party. And yet, Microsoft had resources, visionary leadership, and was able to pivot quickly and compete aggressively. Microsoft came from behind, and ultimately win overwhelming market share, beating the startups (Netscape) and large competitors (IBM) alike — a great example of effective defensive innovation.

the types and cost of innovation

Too often, innovation is described as an unbridled good — something that we should desire for its own sake. The reality is that in any mature organization, innovation has a significant cost, and those costs are rising. At the end of the day, you will be throwing away something — processes, channels, products or product lines, capital equipment, or at the very least time and money that could be devoted to something else — in a speculative bet on something unproven. No sane manager would do a re-org for fun. No sane process engineer would throw away a working, dialed-in process on a lark. There are really only two good reasons to innovate: because you have to, or because the potential upside drastically outweighs the cost of failure and the cost of that failure will be manageable. Or both.

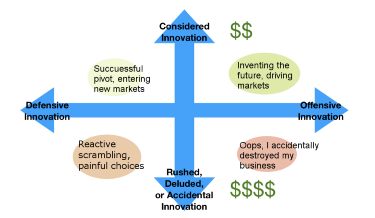

Unfortunately, sometimes we get pressured into innovation out of fear, or we stumble into a new way of doing things without thinking it through, or we rush into adopting something new because we fall in love with an idea or a technology. Regardless of the cause, whether driven by fear or cluelessness or irrational exuberance, we may find ourselves plunging forward with a half-baked plan, or no plan at all. This typically doesn’t end well. Consider the following chart:

an innovation quad chart — offensive vs defensive, considered vs. rushed, accidental, or deluded.

defensive vs. offensive Innovation

Defensive innovation happens because something is radically broken, or someone else is eating your lunch. Necessity, as they say, is a mother. If you are standing on a burning platform, you might jump off as an alternative to certain destruction. Pivot, pivot! Defensive innovation can also be thoughtful and strategic, as the case study of Microsoft and Internet Explorer demonstrates.

Offensive innovation is when you are innovating to get ahead of where you and the rest of the market or industry are. Offensive innovation is the type of innovation that creates entirely new markets, that shapes the future of industries, or creates new ones. And while new technology often plays a part in successful offensive innovation, it is typically not the driver. Innovations in design, system engineering, marketing, regulatory change, or business model are at least as likely to be innovation drivers as technology innovation in successful offensive innovation.

The point about new technology not being the driver of innovation may sound counter intuitive, and deserves a bit more expansion.

innovation case study: the Apple iPad and the “invention” of the tablet computer

Consider the iPad — in the eyes of many Apple “invented” tablet computing with the iPad. No such thing is true. Prior to the iPad there was Apple’s unsuccessful Newton product, and before the Newton was the truly revolutionary Psion Organizer — a technical marvel from the 80s that failed to gain market traction. And I could go on to list more early tablet computers and their technical antecedents. The point is that nobody remembers these predecessors because they didn’t go anywhere. The products weren’t successful enough to drive large-scale change — one of the hallmarks of successful offensive innovation.

Mediocre innovators borrow. Great innovators steal. Apple “invented” tablet computing with the iPad because Apple was able to integrate existing technical and functional capabilities with design and marketing that made a compelling product with mass appeal. Put another way, the driving innovation of the iPad was systems engineering, design, and marketing, not technology. And because they were the successful, offensive innovator in that space, Apple created an entirely new market, “inventing” tablet computing. By then, most of the underlying technology was old hat. Not that anybody remembers that, or cares.

considered vs. rushed (or accidental) innovation

It’s a truism that rushed planning or execution is more expensive and wasteful, and less likely to succeed. But sometimes innovation happens without any real planning at all — consider the digital camera. Had Kodak really thought through the implications of digital photography for the film business they might have killed the project, or gotten ahead of the trends that would destroy their core business. But the implications of real innovation can be very hard to predict. Even a seemingly minor innovation can trigger big disruption.

So, treat any non-incremental change as a potentially disruptive element, potentially dangerous as well as beneficial. Which leads me the most important consideration: is now the right time for innovation? You may not be able to control the timing if you are innovating defensively, but when innovation is optional, the timing is critical. Can you wait for another quarter or another year and make steady money with incrementalism, increasing the risk that someone else will disrupt you, or do you innovate now in an attempt to drive the market, understanding the potential costs and risks?

So, want to learn practical strategies for managing the cost of innovation while maximizing impact? This is the subject of an upcoming essay — the next in this series.

conclusions

Innovation is a frequently misunderstood topic. The feeling of newness and incremental change is often mixed up with real innovation, the kind of truly disruptive change that turns industries upside down. While it isn’t always possible to predict what will cause such an upset, the one thing we can be sure of is that the disruptive change will come. You can either drive this change, react to it, or be overwhelmed by it.

We can categorize innovation as offensive or defensive, depending on whether we are innovating to get ahead of an industry or innovating to keep up with external disruptive changes. We can also categorize innovation as considered or not. At the end of the day, a considered approach to innovation is critical to maximizing the cost of innovation and likelihood of long-term success. Managing the cost of innovation will be the subject of the next essay in this series.

And while innovation gets all the attention, incrementalism is an excellent strategy for value creation. Indeed, incremental improvement is where much of the world’s value comes from. However valuable incrementalism is for building value day-to-day, it is brittle in the face of disruptive change.

Organizations that are successful and comfortable with incrementalism typically embody culture and processes that reject innovation as an existential threat. This isn’t a problem that is solved simply by having an amazing corporate research lab, as we have seen through the examples of Kodak and Xerox PARC. Both organizations effectively invented the future of their industries, and both completely failed to capitalize on their inventions because the larger organizational culture rejected their own innovation.

Thus, many of the inventors or creators of disruptive innovation have failed to benefit from their own innovations. But hope is not lost, as we also have examples of innovative organizations that have successfully capitalized on offensive or defensive innovation, such as Alphabet’s X in the 2010s or Microsoft of the late 90s and early 2000s. The key differentiator is innovation culture and leadership — the subject of an upcoming essay.

下载开源日报APP:https://openingsource.org/2579/

加入我们:https://openingsource.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://openingsource.org/about/love/

今天的项目挺好玩的