每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg

今日推荐开源项目:《可视化的面向对象语言——Luna》

推荐理由:Luna 语言是一个尚待完善的面向对象语言,它最大的特点是尝试用可视化的方式将程序的进程表现出来。在最常见的情况下,每个节点对应一行代码。

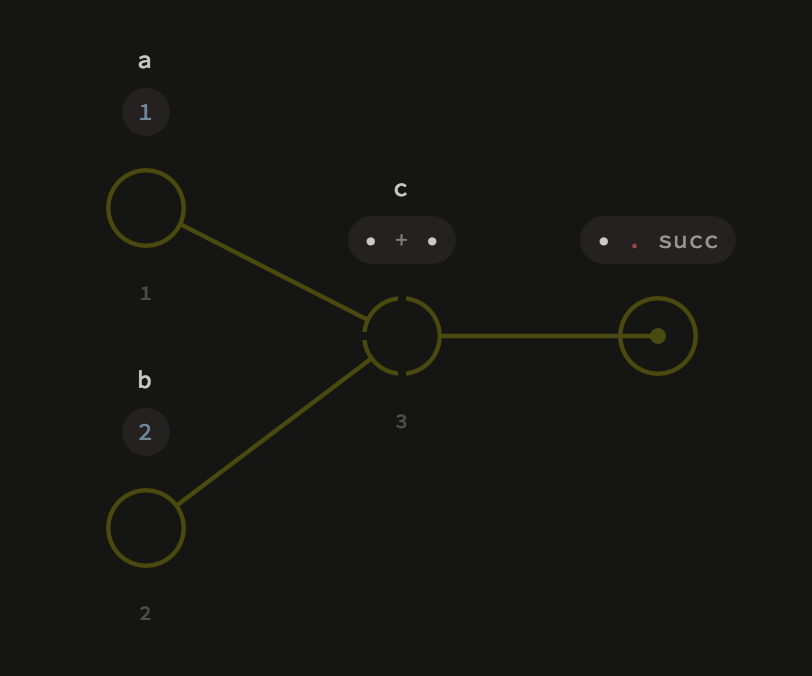

例如下图

它的对应Luna代码是

a = 1 b = 2 c = a + b c.succ

从这里我们可以看出,节点实际上将一行代码分为两部分:等号左边和等号右边。等号左边是要处理的变量名,右边则是对于表达式。

最左边的两个节点对应于行a = 1和b = 2。变量名称a,b成为其相应节点的名称,数字1和2它们的定义。他们没有输入端口和每个输出端口。

中间的节点对应于该行c = a + b。它具有a和b连接到它的输入节点。由此,可以清楚地看到输入数据来自哪里。

最右边的节点对应于该行c.succ。该节点没有名称,因为相应的行没有定义任何变量。它有c连接到它的self端口的节点。这个端口表示方法调用的目标。

我们可以看到,链接各个节点的线条颜色是黄色,这代表的是数据的类型。黄色是整型,橙色是浮点型( Luna 中被称为real),紫色是字符串型,列表(数组)是蓝色,含有多种数据类型的列表是绿色。每个节点的左端代表输入,右端代表输出。

数据类型:

就 Luna 目前的数据类型及处理来看,想要成为一门合格的面向对象的可视化语言还亟待完善。

Luna 目前支持三种基本数据类型:整型,真值(即浮点型),字符串,但三者直接的转换如1+1.5这种表达式尚不能被实现,因此在用于数据处理方面的话还较为麻烦。

关于自定义数据类型:

与 python 类似, Luna 可以靠类生成一个新对象,以此达到使用自定义数据类型的目的。

对象在 Luna 里具有不可变性。也就是说在其他语言里,你可能会使用counter.count += 1去改变对象。而在 Luna 里,如果你写foo = Circle 15.0, 无论如何使用它,foo将永远是Circle 15.0,除非你重定义foo。

构造类与方法:

以下是构造类和方法的文本说明:

class Shape: Circle: radius :: Real Rectangle: width :: Real height :: Real def perimeter: case self of Circle r: 2.0 * pi * r Rectangle w h: 2.0 * w + 2.0 * h def area: case self of Circle r: pi * r * r Rectangle w h: w * h

总结:

主要优势:

作为一款新型的可视化编程语言, Luna 更关注于数据的处理,这可以使任何需要使用计算机辅助进行数据处理的人都能快速的使用 Luna 进行编程。

主要缺陷:

目前的 Luna 在类和对象方面还有所欠缺。目前,没有办法使用可视化编辑器定义类和方法。

个人感觉 Luna 为了图形化程序流程在代码的灵活性上作出了很大的妥协,以至于cos=sin=5这样的连等表达式都无法一行写出,这对笔者这种喜爱语法糖的人来说还是比较不友好的QAQ,不过 Luna 本身侧重的就是那些有数据处理需求而又不太对编程或者说语法感冒的设计者,有兴趣的同学还是可以去 GitHub 上学习一下的。

此外:Luna的基础语法以及操作都在官方文档里有详细的解释

https://luna-lang.gitbooks.io/docs/content/visual_representation.html

今日推荐英文原文:《Who really owns an open project?》作者:

推荐理由:很多人不太了解开源社区是如何运作的,比如说,一个开源项目真正意义上属于谁?一个典型例子是: Linus 是 Linux kernel 的作者,然后将其开源,然后更多的人加入进来这个项目贡献代码,还有做非代码工作的志愿者,还有捐赠者,那么谁可以“拥有”这个开源项目呢?这个项目到底属于谁呢?

老实说,这个问题挺复杂的,在探讨这个问题之前,我们还得定义:什么叫“拥有一个项目”,是知识产权?还是可以决定它的发展,还是创造了这个项目,还是可以毁灭这个项目,才叫“拥有”呢?

Who really owns an open project?

Differences in organizational design don't necessarily make some organizations better than others—just better suited to different purposes. Any style of organization must account for its models of ownership (the way tasks get delegated, assumed, executed) and responsibility (the way accountability for those tasks gets distributed and enforced). Conventional organizations and open organizations treat these issues differently, however, and those difference can be jarring for anyone hopping transitioning from one organizational model to another. But transitions are ripe for stumbling over—oops, I mean, learning from.

Let's do that.

Ownership explained

In most organizations (and according to typical project management standards), work on projects proceeds in five phases:

- Initiation: Assess project feasibility, identify deliverables and stakeholders, assess benefits

- Planning (Design): Craft project requirements, scope, and schedule; develop communication and quality plans

- Executing: Manage task execution, implement plans, maintain stakeholder relationships

- Monitoring/Controlling: Manage project performance, risk, and quality of deliverables

- Closing: Sign-off on completion requirements, release resources

The list above is not exhaustive, but I'd like to add one phase that is often overlooked: the "Adoption" phase, frequently needed for strategic projects where a change to the culture or organization is required for "closing" or completion.

- Adoption: Socializing the work of the project; providing communication, training, or integration into processes and standard workflows.

Examining project phases is one way contrast the expression of ownership and responsibility in organizations.

Two models, contrasted

In my experience, "ownership" in a traditional software organization works like this.

A manager or senior technical associate initiates a project with senior stakeholders and, with the authority to champion and guide the project, they bestow the project on an associate at some point during the planning and execution stages. Frequently, but not always, the groundwork or fundamental design of the work has already been defined and approved—sometimes even partially solved. Employees are expected to see the project through execution and monitoring to completion.

Employees cut their teeth on a "starter project," where they prove their abilities to a management chain (for example, I recall several such starter projects that were already defined by a manager and architect, and I was assigned to help implement them). Employees doing a good job on a project for which they're responsible get rewarded with additional opportunities, like a coveted assignment, a new project, or increased responsibility.

An associate acting as "owner" of work is responsible and accountable for that work (if someone, somewhere, doesn't do their job, then the responsible employee either does the necessary work herself or alerts a manager to the problem.) A sense of ownership begins to feel stable over time: Employees generally work on the same projects, and in the same areas for an extended period. For some employees, it means the development of deep expertise. That's because the social network has tighter integration between people and the work they do, so moving around and changing roles and projects is rather difficult.

This process works differently in an open organization.

Associates continually define the parameters of responsibility and ownership in an open organization—typically in light of their interests and passions. Associates have more agency to perform all the stages of the project themselves, rather than have pre-defined projects assigned to them. This places additional emphasis on leadership skills in an open organization, because the process is less about one group of people making decisions for others, and more about how an associate manages responsibilities and ownership (whether or not they roughly follow the project phases while being inclusive, adaptable, and community-focused, for example).

Being responsible for all project phases can make ownership feel more risky for associates in an open organization. Proposing a new project, designing it, and leading its implementation takes initiative and courage—especially when none of this is pre-defined by leadership. It's important to get continuous buy-in, which comes with questions, criticisms, and resistance not only from leaders but also from peers. By default, in open organizations this makes associates leaders; they do much the same work that higher-level leaders do in conventional organizations. And incidentally, this is why Jim Whitehurst, in The Open Organization, cautions us about the full power of "transparency" and the trickiness of getting people's real opinions and thoughts whether we like them or not. The risk is not as high in a traditional organization, because in those organizations leaders manage some of it by shielding associates from heady discussions that arise.

The reward in an Open Organization is more opportunity—offers of new roles, promotions, raises, etc., much like in a conventional organization. Yet in the case of open organizations, associates have developed reputations of excellence based on their own initiatives, rather than on pre-sanctioned opportunities from leadership.

Thinking about adoption

Any discussion of ownership and responsibility involves addressing the issue of buy-in, because owning a project means we are accountable to our sponsors and users—our stakeholders. We need our stakeholders to buy-into our idea and direction, or we need users to adopt an innovation we've created with our stakeholders. Achieving buy-in for ideas and work is important in each type of organization, and it's difficult in both traditional and open systems—but for different reasons.

Penetrating a traditional organization's closely knit social ties can be difficult, and it takes time. In such "command-and-control" environments, one would think that employees are simply "forced" to do whatever leaders want them to do. In some cases that's true (e.g., a travel reimbursement system). However, with more innovative programs, this may not be the case; the adoption of a program, tool, or process can be difficult to achieve by fiat, just like in an open organization. And yet these organizations tend to reduce redundancies of work and effort, because "ownership" here involves leaders exerting responsibility over clearly defined "domains" (and because those domains don't change frequently, knowing "who's who"—who's in charge, who to contact with a request or inquiry or idea—can be easier).

Open organizations better allow highly motivated associates, who are ambitious and skilled, to drive their careers. But support for their ideas is required across the organization, rather than from leadership alone. Points of contact and sources of immediate support can be less obvious, and this means achieving ownership of a project or acquiring new responsibility takes more time. And even then someone's idea may never get adopted. A project's owner can change—and the idea of "ownership" itself is more flexible. Ideas that don't get adopted can even be abandoned, leaving a great idea unimplemented or incomplete. Because any associate can "own" an idea in an open organization, these organizations tend to exhibit more redundancy. (Some people immediately think this means "wasted effort," but I think it can augment the implementation and adoption of innovative solutions. By comparing these organizations, we can also see why Jim Whitehurst calls this kind of culture "chaotic" in The Open Organization).

Two models of ownership

In my experience, I've seen very clear differences between conventional and open organizations when it comes to the issues of ownership and responsibility.

In an traditional organization:

- I couldn't "own" things as easily

- I felt frustrated, wanting to take initiative and always needing permission

- I could more easily see who was responsible because stakeholder responsibility was more clearly sanctioned and defined

- I could more easily "find" people, because the organizational network was more fixed and stable

- I more clearly saw what needed to happen (because leadership was more involved in telling me).

Over time, I've learned the following about ownership and responsibility in an open organization:

- People can feel good about what they are doing because the structure rewards behavior that's more self-driven

- Responsibility is less clear, especially in situations where there's no leader

- In cases where open organizations have "shared responsibility," there is the possibility that no one in the group identified with being responsible; often there is lack of role clarity ("who should own this?")

- More people participate

- Someone's leadership skills must be stronger because everyone is "on their own"; you are the leader.

Making it work

On the subject of ownership, each type of organization can learn from the other. The important thing to remember here: Don't make changes to one open or conventional value without considering all the values in both organizations.

Sound confusing? Maybe these tips will help.

If you're a more conventional organization trying to act more openly:

- Allow associates to take ownership out of passion or interest that align with the strategic goals of the organization. This enactment of meritocracy can help them build a reputation for excellence and execution.

- But don't be afraid sprinkle in a bit of "high-level perspective" in the spirit of transparency; that is, an associate should clearly communicate plans to their leadership, so the initiative doesn't create irrelevant or unneeded projects.

- Involving an entire community (as when, for example, the associate gathers feedback from multiple stakeholders and user groups) aids buy-in and creates beneficial feedback from the diversity of perspectives, and this helps direct the work.

- Exploring the work with the community doesn't mean having to come to consensus with thousands of people. Use the Open Decision Framework to set limits and be transparent about what those limits are so that feedback and participation is organized ad boundaries are understood.

If you're already an open organization, then you should remember:

- Although associates initiate projects from "the bottom up," leadership needs to be involved to provide guidance, input to the vision, and circulate centralized knowledge about ownership and responsibility creating a synchronicity of engagement that is transparent to the community.

- Ownership creates responsibility, and the definition and degree of these should be something both associates and leaders agree upon, increasing the transparency of expectations and accountability during the project. Don't make this a matter of oversight or babysitting, but rather a collaboration where both parties give and take—associates initiate, leaders guide; associates own, leaders support.

Leadership education and mentorship, as it pertains to a particular organization, needs to be available to proactive associates, especially since there is often a huge difference between supporting individual contributors and guiding and coordinating a multiplicity of contributions.

每天推荐一个 GitHub 优质开源项目和一篇精选英文科技或编程文章原文,欢迎关注开源日报。交流QQ群:202790710;电报群 https://t.me/OpeningSourceOrg