今日推荐开源项目:《日历 fullcalendar》

今日推荐英文原文:《The pleasure of finding things out》

今日推荐开源项目:《日历 fullcalendar》传送门:项目链接

推荐理由:Fullcalendar 是一款用来管理日程安排、工作计划的日历工具。它的功能强大而且实用,特点在于它的许多功能都很轻松地自定义,轻量,适合开发人员,并且开源。可通过npm安装。

今日推荐英文原文:《The pleasure of finding things out》作者:Samuel Flender

原文链接:https://medium.com/think-like-a-physicist/the-pleasure-of-finding-things-out-fd97abb61dfb

推荐理由:这是科研工作者的浪漫。

The pleasure of finding things out

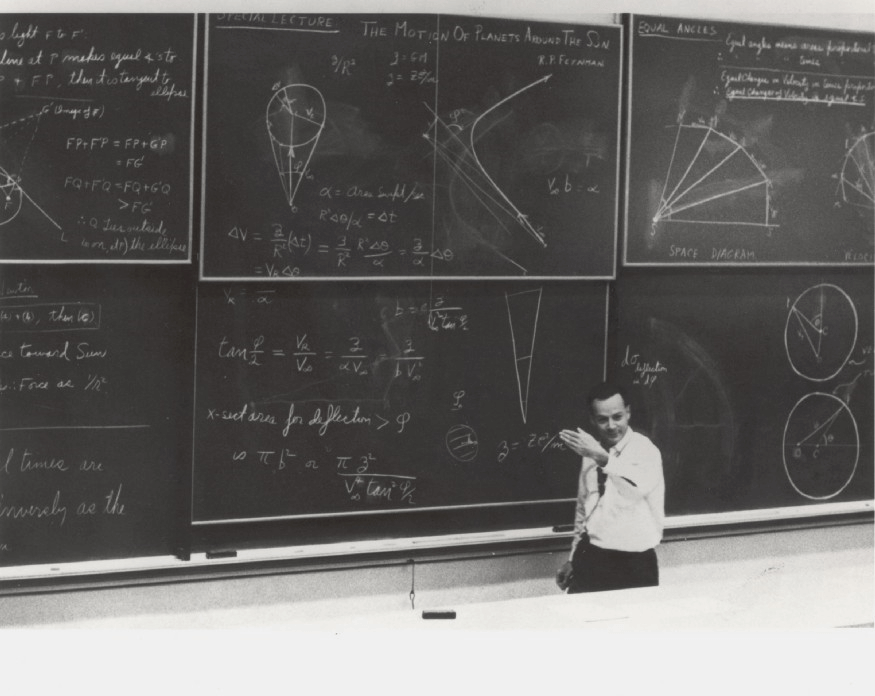

4 lessons from Richard Feynman

(Richard Feynman giving a lecture at Caltech (source))Richard Feynman was one of the greatest physicists and thinkers of all time. “The pleasure of finding things out” provides a deep insight into Feynman’s thought process with interviews, speeches, lectures, and articles. Here are my top 4 take-aways from the book.

1. The discovery matters, not the honors

Even though Feynman received the Nobel price in Physics for the development of quantum electrodynamics, he makes it a point that academic honors, prices, and titles bother him. He believes that the true reward of scientific work is the discovery itself:“I don’t see that it makes any point that someone in the Swedish Academy decides that this work is noble enough to receive a prize — I’ve already got the prize. The prize is the pleasure of finding the thing out. The honors are unreal to me.”

On that note, Feynman has a fitting anecdote. In high school he was chosen to become a member of the Arista club, a group of kids with outstanding grades. He discovered that the main purpose of the club was to meet and decide which other students are worthy enough to become members as well, which he found pointless and frustrating.

Later in his life, he had a similar experience with becoming a member of the National Academy of Sciences, from which he ultimately resigned because, in his words, “that was just another organization most of whose time was spent in choosing who was illustrious enough to join”.

It’s the scientific discovery that matters, not the honors.

2. The right way and the wrong way to report scientific results

Feynman is passionate about how science should be done, and where it goes wrong. For instance, what’s the right way to report results from a scientific experiment? Feynman:“Disinterestedly, so that the other man is free to understand precisely what you are saying, and as nearly as possible not covering it with your desires.”

The problem in scientific publishing is that authors have all the incentive to leave out pieces that might cast doubt, and exaggerate pieces that confirm their view. Scientific publishing is therefore intrinsically prone to bias.

The antidote to this bias, Feynman argues, is rigorous scientific integrity: committing to publishing the experimental results, no matter the outcome, prior to the start of the experiment, and publishing every piece of data, no matter how favorable it is. Scientific integrity means disinterest in the appearance.

Science is, in this sense, the opposite of advertising, Feynman remarks. If you see scientific papers that feel like pure advertisement, you should see red flags. On that note, politics can be particularly hazardous to scientific integrity. If the scientist’s answer happens to align with a stakeholder’s political agenda, they can leverage that answer for their own benefit. If it does not, they can sweep it under the rug. When this happens, scientists are merely ‘used’, Feynman remarks in his 1974 Caltech commencement address. Further:

“So I wish you the good luck to be somewhere where you are free to maintain the kind of integrity I have described, and where you do not feel forced by a need to maintain your position in the organization, or financial support, or so on, to lose your integrity.”

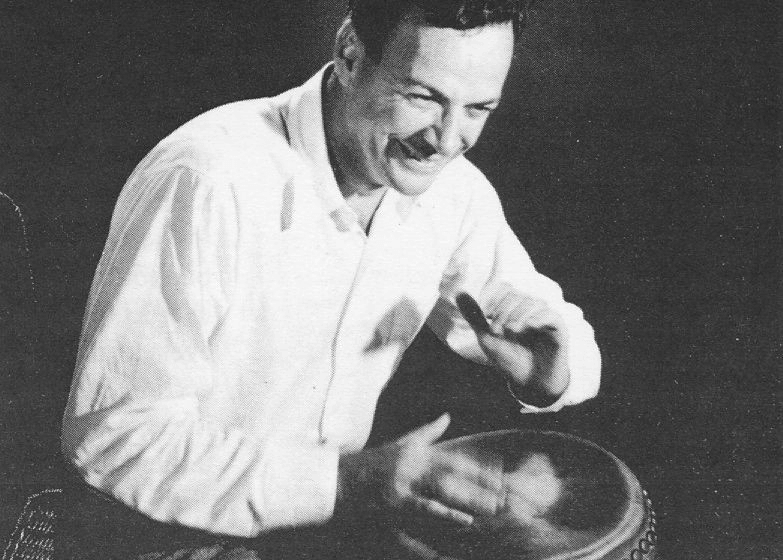

(Feynman playing the Conga (source))

3. Science is the belief in the ignorance of experts

Feynman observes that scientists tend to fear deviating from results that have been previously established by experts. Robert Millikan, for instance, measured the electron’s charge by an experiment with falling drops of oil. His result was flawed because he assumed an incorrect value for the viscosity of air. Yet, if you look at the experimental results after Millikan, you find that one is a little bigger than Millikan’s, and the next one’s a little bigger than that, until finally they settle down to a number which is higher. Feynman explains that when scientist found a value that was too far off the original result, they looked hard to find some flaw in the experiment that would bring the number down, but not so if their results was in line with the original.In contrast, Feynman made it a point to give his honest opinion no matter who he was speaking to. In an interview he remarks on his encounter with Niels Bohr, winner of the 1922 Nobel price in Physics, while working on the Manhattan project. In a meeting, Feynman was the only scientist who challenged Bohr’s ideas on how to make the atomic bomb more efficient. Feynman remarks on that encounter:

“I was always dumb about one thing, I never knew who I was talking to. I was always worried about the physics; if the idea looked lousy, I said it looked lousy.”

Bohr reportedly respected that attitude, making it a priority to meet with Feynman first to discuss new ideas. Bohr:

“He’s the only guy who’s not afraid of me, and will say when I’ve got a crazy idea. So next time when we want to discuss ideas, we’re not going to do it with these guys who say everything is yes, yes, Dr. Bohr.”

4. Beware of cargo cult science

Cargo cults exist on the pacific islands. During the war these tribes saw airplanes land filled with goods, and they wanted to make the same thing happen after the war was over. So they arranged runways lit by fires, and a wooden hut for a man to sit in, wearing fake headphones made of bamboo. The islanders believed that they could ‘make’ planes land by following the procedures they had seen before.‘Cargo cult science’ is a phrase coined by Feynman, referring to the practice of professionals mirroring scientific work, but not producing any valuable insights. He frequently labels the social sciences as a form cargo cult science:

“Social science is an example of a science which is not a science. They don’t do things scientifically, they follow the forms, but they don’t get any laws, they haven’t found anything.”

Case in point, we know today that many psychological studies that have been done over the past decades fail the reproducibility test.

What distinguishes real science from cargo cults is, once again, a habit of rigorous scientific integrity: publishing the results in an unbiased manner, making sure all independent variables are accounted for, and listing all things that could possibly invalidate the scientist’s hypothesis.

Bonus: Feynman’s predictions that came true

When working through the book, I noticed three implicit predictions that Feynman made, all of which (curiously) came true:+ on chess-playing machines: “Make a machine to play Go efficiently!” — said in 1985, 30 years before AlphaGo. + on launching rockets: “Any outside competition would have all the advantages of starting over” — said in the 1980s, decades before SpaceX and Blue Origin. + on the masses of particles: “Well, there are the masses of particles: the gauge theories give beautiful patterns for the interactions, but not for the masses, and we need to understand this irregular set of numbers.” — said in 1979, decades before the discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012.

下载开源日报APP:https://openingsource.org/2579/

加入我们:https://openingsource.org/about/join/

关注我们:https://openingsource.org/about/love/